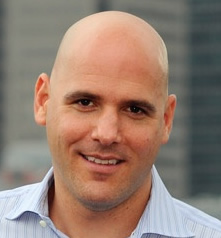

Last week, for a conference in San Francisco, I was asked to interview Jeff Clavier, the straight-shooting founder of the early-stage investment firm SoftTech VC. We were tasked with addressing the so-called Series A crunch and its ripple effects. As part of that chat — edited here for length — Clavier volunteered some interesting tidbits, including how to prepare startups for their next round of funding, and the most ruthless firm on Sand Hill Road.

Last week, for a conference in San Francisco, I was asked to interview Jeff Clavier, the straight-shooting founder of the early-stage investment firm SoftTech VC. We were tasked with addressing the so-called Series A crunch and its ripple effects. As part of that chat — edited here for length — Clavier volunteered some interesting tidbits, including how to prepare startups for their next round of funding, and the most ruthless firm on Sand Hill Road.

You aim for a certain ownership percentage with each deal. Do things usually go as planned? I hear of uncomfortable situations cropping up between Series A and earlier investors.

When you invest at the seed round, you have the legal right to maintain ownership provided that you clear the hurdle of being a major investor, and we always ask to be a major investor and have pro rata rights. However it’s true that there are some Series A firms on Sand Hill – I won’t mention any names but one that comes to mind starts with an S – that always try to cut you out of your pro rata ownership because they always want to take as big a chunk as possible of Series A rounds. They typically want something in the 30 percent range.

If you want to take 30 percent and let insiders take their pro rata, that’s going to be a pretty dilutive round for the founders, so there are some games that they play. The way to counter the game is to organize a bit of a process where you can have multiple firms submitting term sheets, then figure out which is most interesting and the fairest to the founders as well as the insiders.

Are you seeing more Series A firms try to elbow seed-stage investors out of the picture entirely?

Yes, the “piggy” round. . . We have seen entrepreneurs take these rounds in lieu of a seed round – mostly people who’ve been around the block once or twice — and if there’s enough conviction from the VC to help entrepreneurs with the earliest stages of their companies’ life, it’s great for the entrepreneurs.

Is that true from an equity standpoint, too? I wonder whether it’s good that — with so many seed and post-seed rounds today — entrepreneurs have given investors 20 percent of their startups before they even reach a Series A financing.

It’s actually more than that. The seed round dilution is typically 20 to 25 percent dilution, plus [there’s the issue of] the option pool, meaning reserves for future hires. When you tack on your Series A – and some firms try to get 25 to 30 percent ownership for themselves, then you have the add-on of the insiders pro rata, which can be five to seven percent – those two rounds can be pretty dilutive.

What we’ve seen with companies that are doing really well and are sort of “hot” is the percentage target of the Series A investor will go from 25 to 30 percent to 20 to sometimes 15 percent, because when you’re in a competitive situation, paying up is not the only way. Being easy to deal with and friendly from a term sheet perspective is also a way to win those competitive situations.

So really only the hottest entrepreneurs are not getting screwed.

I wouldn’t say screwed. If you can [run your company without outside investors and it’s a hit], you’re home free. [If you can’t], it’s really the support and help that you’re going to get alongside the cash that makes a fundamental difference in the seed-to-Series-A journey. You pay in dilution for what you get in terms of capital and support.

Given that it’s your biggest challenge, how do you help your seed-funded companies nab Series A funding?

Part of it is understanding the market dynamic. You know that some firms like to meet startups very early on and create relationships over a year, for example, like our friends at Emergence Capital. They love to meet companies way ahead of any fundraising, so roughly a year before we know we’ll have to fundraise, we’ll either introduce our companies to them or they’ll ping us, because they’re pretty good at that. Then, a year later, we’ll [reach out to say], “They’re thinking of doing a round, we’d love to get your feedback,” wink, wink.